This creepy looking motherfucker.

Now, the way it has been described to me:

"Henry James brought the horror genre into the realm of the domestic."

-Kate SkoretzWhat does that mean?

Well, it may be necessary to give a primer on horror.

Horror and Terror are dynamic states.

We love horror movies, yes?

But, what makes them so lovable?

The preceding terror.

Terror is the moment(s) preceding the horrible realization.

So it is terror that we feel in anticipation of the awful.

Horror follows afterwards.

See the difference?

Apparently Charles Darwin did (Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals).

Paul Ekman would have a field day.

For those not in the know, he is the guy Timothy Roth plays on Lie to Me:

Enough references?

Moving on.

So what does this have to do with anything?

Well, understanding that horror and terror are techniques used as a style is important and that they are dynamic traits of story.

I would like to introduce another, that I associate very closely with the horror genre:

The Uncanny.

Otherwise known as the opposite of what is familiar.

Uncanniness is the ability to take something that is familiar and make it unfamiliar.

Another word might be strange.

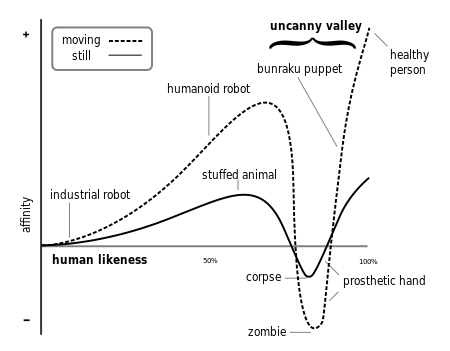

This is also an excuse to use one of my favorite graphs on the internets:

So we take what is familiar and compare it to human likeness.

Now, as we move from something that isn't human, an industrial robot, we do not perceive it as familiar or comforting i.e. this guy:

Not terribly terrifying, but not very comforting either.

Kind of meh, wouldn't you say?

Opposite side we have a healthy person:

Nope. Not for a second.

Better.

We find this familiar, not terrifying, kind of strong and sure....what was I saying?

So what about in the middle?

Well, we get things like this:

The more closely something approximates a human, the more we like it.

The more familiar it is.

However, there comes a point where there is a dip in our familiarity with objects and their humanness.

For example, has anyone seen a Real Doll?

No?

What you see is a silicone doll meant to simulate the human body as accurately as possible.

If you aren't feeling uneasy then you watched Lars and the Real Girl one too many times.

(I'm with the folks on the left.)

Now, the premise of the movie comes from a man purchasing a lifelike doll off the internet to help him deal with his intimacy issues.

No one here can relate...

Point being, the movie is based on the premise of the what is known as the Uncanny Valley.

The more lifelike something appears to be, the less we trust it.

Now, how does this apply to the horror genre?

Well, if you peak at the chart located above...ah fuck it.

Look at the chart, the bottom most dip.

What do you see?

Well, the most uncanny thing is not in fact a corpse.

A corpse we understand, but it is most human-like, but one of the least familiar.

It is also non-moving, which we understand.

CSI is predicated on this:

She will not jump at Laurence Fishburne except in the outtakes.

Why?

It would be a different genre.

However, add a little movement to a corpse and what do you get?

Basically every horror monster ever:

I'm not kidding.

All day!

Something about the uncanny makes our hair stand completely on end.

So why is this so important to Henry James' work?

Well, he managed to do something that no one else had done before.

If you read the original horror stories like Dracula and Frankenstein, you will notice something particular about their writing:

It is always set in far away lands or something about the faraway comes spilling over.

Transylvania's residents are foreign to England, the foreigner is a shambling corpse, who needs his own dirt in order to survive.

Dracula is basically an alien from outer space.

Same with Frankenstein and his monster.

He is a doctor, creating a simulacrum of a person, and where does the story end? In the icy reaches of the north.

So what is different about Henry James?

He made the domestic uncanny.

If the most effective strategy for horror is by making the familiar strange,

Henry James worked by making the strange familiar.

In Turn of the Screw, a down and out governess is hired to take care of an estate in the country.

It is isolated, it is secluded, but for pity's sake, it is England!

Who are the MacGuffins in this piece? Children. Nothing more, nothing less. Darling, creepy children.

(For those who do not know, MacGuffins are plot devices, used to drive plot forward, something for the protagonist/antagonist to obtain for often no explained reason...they could have been hats).

The main antagonists are ghosts.

Now, where do ghosts and horrible things happen?

Well, until Henry James, out in foreign lands, away from civilization and prying eyes.

So it must have been quite a shock to have ghosts of domestic servants come back and haunt a (literally) unnamed governess in an occupied country home.

So it was shocking, it was surprising, it was terrible.

By setting the story and the main conflict and the main antagonists as things or persons or entities that one may encounter in one's own home, James was able to remove the romance from the horror genre.

It became something much more familiar and therefore, all the more uncanny and unnerving.

It may just be that Henry James is sitting on the opposite side as the Romantics on the uncanny valley, but it is interesting to examine how the story works from a horror standpoint.

Therefore, in working with this particular text, we are seeking to do something similar.

It is quite difficult in a modern age to not do period piece horror stories.

They do so remarkably well, what with The Awakening, The Woman in Black, etc.

However, I don't foresee a staged reading of the novel as it is, nor, an adaptation of lifted text in period dialect and costume would really do this piece justice.

For one, it is a terrible script.

And two, it doesn't have the same effect as James' manuscript.

In it, the governess is the sole perspective through which the audience perceives the world (exempting the prologue).

We look through her eyes as it were.

So in the manuscript, we are dependent on her subjective viewpoint.

However, onstage, we are less bound by what is told to us and more by what we see and perceive.

There is an objective element to the drama of what the governess (actress) physically does.

So those are the questions we are currently considering.

How best to make/use the genre as Henry James did (by making the strange familiar)?

And

From what perspective should we tell the story? e.g. the governess, the audience.

I have some ideas on how to do this that I will discuss in my next post.

For now, suffice it to say, it will probably be an examination of unreliable narrators.

No comments:

Post a Comment